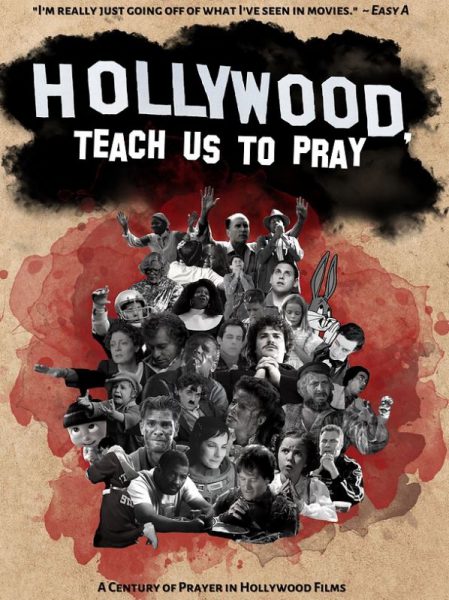

Featured Image: “Hollywood, Teach Us to Pray“ movie poster.

Terry Lindvall | Courtesy

VWU Professors Minnis and Lindvall unveil new movie about the history of prayer in Hollywood.

On Feb. 28 at 7 p.m., the campus community was able to view Virginia Wesleyan faculty Dr. Terry Lindvall and Dr. Stu Minnis’ documentary film “Hollywood, Teach Us to Pray.” Being open to the university, it was the first time the film had premiered besides the showing of it at the Naro Expanded Cinema in downtown Norfolk on Feb. 5.

Although the film was relatively new to the Wesleyan audience as a whole, the production of it has extended many years back, all the way to 2006 when Lindvall presented a workshop on the general topic of it at the 19th Annual Virginia Film Festival.

Following that, he wrote a book titled “God on the Big Screen: A History of Hollywood Prayers from the Silent Era to Today” in 2019 which led to him creating the film itself.

The structure of the film begins with scenes of people calling out to God for all sorts of things from needing help to expression of frustration. It moves through whole prayers themselves and concludes with “amens.” “If you follow the movie itself, it is a prayer,” Lindvall said.

In talking about his inspiration for the idea of looking at the correlation between prayer and movies, Lindvall said, “I think my interest in prayer is that there’s probably more prayer in Hollywood movies than there is at Virginia Wesleyan, except at final exam times.”

Although prayer is often seen strictly in a religious context, Lindvall posited that the appeal of the film does not rest on whether or not you are religious. Viewers do not have to be Christian to be interested in the subject of Christian prayer in movies.

Lindvall assured that if you are interested in movies in general, it will be engaging to you.

“It’s amazing to see how many films have used prayers in significant ways,” he said.

Minnis, an editor of the documentary film, held a similar viewpoint, agreeing that the film appeals to a wide audience. In 2009, Minnis was a part of the creation process for a different documentary film with fellow faculty member Dr. Steven Emmanuel.

Titled “Making Peace With Vietnam,” Minnis said that it was more of a “conventional documentary structure… You have interviews, and then all the footage surrounding the interviews was footage we shot on the ground in Vietnam.”

The difference with making “Hollywood, Teach us to Pray,” was that there was no pre-existing footage. It is a “clip and interview documentary,” meaning that it consists of a variety of movie scenes interspersed with commentary and explanatory dialogue.

Because the structure of the film’s organization is based upon the exploration of movie clips, multiple genres are represented in the documentary. Pieces from anything like Martin Scorsese’s “Silence,” a historical drama, to the comedy “Table Manners” are featured, allowing for a large range of audience to connect with the material.

Minnis said, “the comedy stuff tends to be what gets the best response, but I tend to like the more serious-minded stuff.” Being able to include both creates a more complete and diversified experience that engages a wide pool of interested viewers.

Lindvall further elaborated upon this point by explaining the value of both the serious and the comedic. “I think that the serious and the comic go side by side. One can be both serious and comic,” Lindvall said.

Comparing this concept to how ideas can be translated throughout languages, he asserted that circumstances could be translated and understood both seriously and comedically, enabling both to be represented in films and for both to be the context for prayer.

Minnis touched upon the significance of being able to share this project that took so much time with the Wesleyan community. Prior to the showing, he said, “I want people… to see it, especially other faculty and students who have heard us talking about working on it for three years now.”

Lindvall was particularly excited for everyone to see the great effort and intention those who worked on it put into it. Eager for people to “realize what an artist Stu Minnis is,” his admiration for the process and labor of the work was clear.

For any who might see the film in the future, Lindvall encouraged them to “stay beyond the credits,” as hidden scenes were concealed at the end of the credits. He said, “It’s like a prayer. Sometimes you think someone’s prayer should be over, but it’s not. The prayer keeps going on and so does the movie.”

By Phoebe Cox

pecox@vwu.edu