The banning of classics such as “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” has been in the public eye for decades, but censorship controversies have only multiplied.

Virginia is currently experiencing turmoil over book banning controversies. Parents, legislators and communities are advocating for books to be removed from schools or restricted from minors in bookstores. Many of the books under fire cover gender identity, sexual diversity and race.

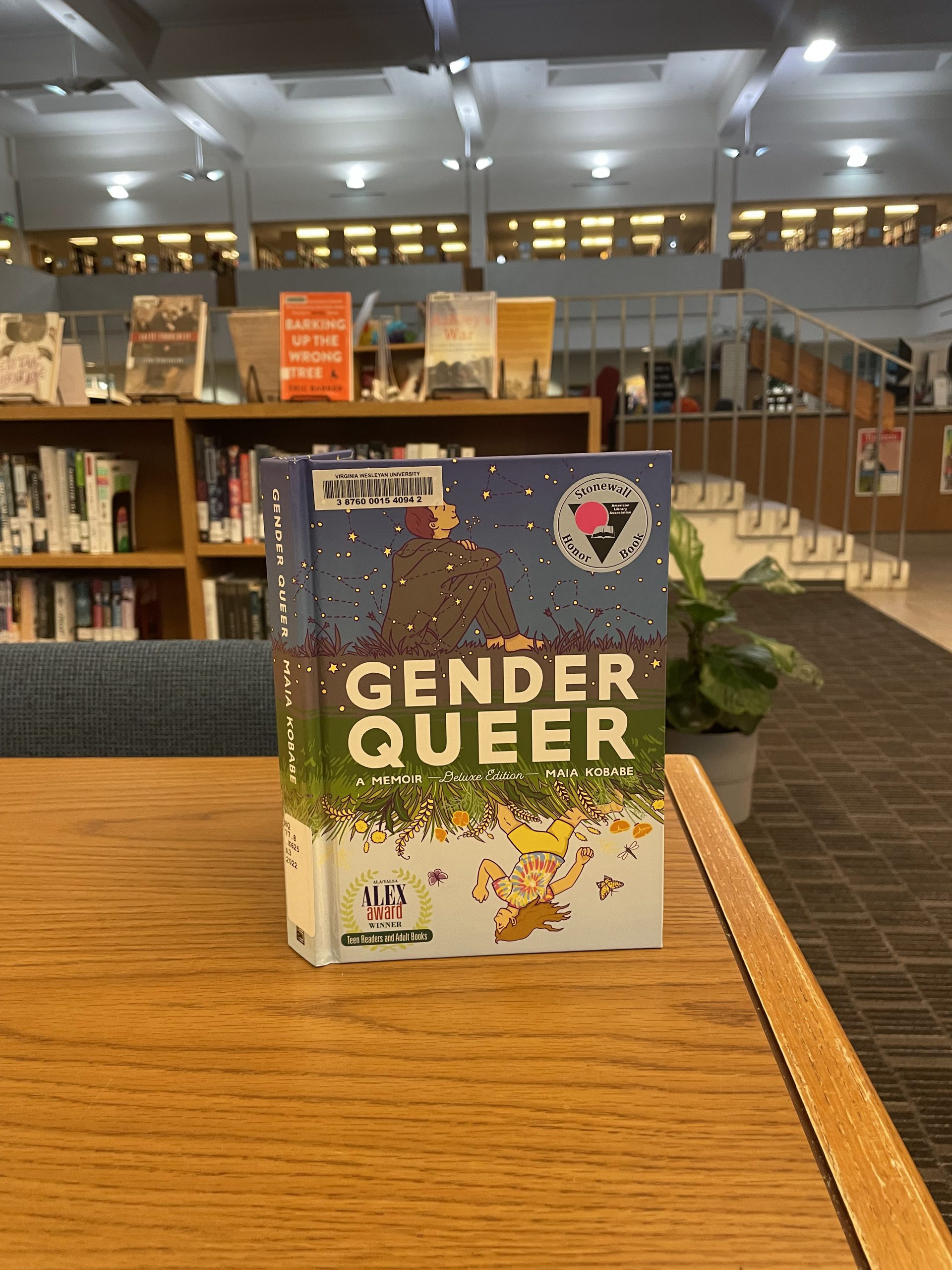

According to an article from The Virginian-Pilot, a recent obscenity case that targeted the sale of two books, “Gender Queer: A Memoir” and “A Court of Mist and Fury,” at Barnes & Noble was dismissed by the Virginia Beach circuit courts on Aug. 30. These titles, and many more, are also being challenged in schools and libraries across Virginia.

While the First Amendment is the focal point of many book banning debates, the reasoning of many in the field of education extends past legality. The impact this may have on students is a prevalent concern.

Victoria “Vicky” Manning, a Virginia Beach School Board member, has been a strong voice on the side of the removal of books from schools. Her advocacy is geared towards removing, as she said in a video posted to Facebook on Aug. 9, what is “pornographic and sexually explicit library books in our schools.” In this same video, she voiced concerns about parents’ inability to monitor what their children are checking out in libraries.

The controversial book “Gender Queer” is available to be read in the Hofheimer Library.

In an email statement, Manning wrote that her view is that “restrictions should be placed on explicit books in school libraries just like we have restrictions on watching explicit movies.” According to Manning, the “books that are being challenged have very explicit pornographic images or language that cannot even be published by the media.” She described the content found in some Virginia Beach Middle Schools available to children as young as 10. Manning said, “Other books give detailed descriptions of sex acts and the excitement it invokes among the characters in the book. Often, these characters are minors.”

“At the very least, there must be an opt-in procedure for parents to elect for their children to read these books,” Manning said.

Students First VA (SFVA), a volunteer organization that Manning helps lead, opposes “any radical indoctrination that takes away control of parents to decide what social issues should be taught to their children,” as well as “any teachings or training based on Critical Race Theory.” The mission of SFVA largely entails removing books they deem sexually explicit from Virginia Beach Middle and High Schools.

On the SFVA blog, they say in a post from July 8 entitled “Over 60 Sexually Explicit Books Found in Virginia Beach Schools” that “This is NOT about book banning but about making sure minors aren’t exposed to harmful materials.” Books Manning has challenged include “Saga (Series Volumes 1-5)” by Brian K. Vaughan and “Fade” by Lisa McMann.

The censorship issue in schools largely includes identifying the line between explicit and informative. This becomes difficult to agree on when such a wide range of perspectives are invested in these decisions.

Dorothy Yanku-Palmer, a junior in the education program at Virginia Wesleyan University, spoke on how censorship could make the creation of lesson plans very difficult for teachers.

“A lot of the materials that are being censored and banned are materials that are actually very beneficial for the lessons,” Yanku-Palmer said.

She also said that topics such as race and LGBT+ identities can be introduced to children early through lighthearted books that feature characters with diverse identities “interacting with one another and having fun.” Tanku-Palmer said,“It is important for children to learn that no matter your race, what you identify as or whatever it may be, that they are all equal.”

Dr. Kathy Merlock Jackson, a professor of Communication at Virginia Wesleyan University, said she thinks it’s important to just get kids reading. She thinks that school districts should be “teaching children to become critical readers and be able to evaluate texts themselves, rather than to eliminate materials that someone deems inappropriate.” According to Jackson, “Books reflect different viewpoints. And that’s what an education is.”

Jackson teaches courses in media studies and has an educational background in American Culture. She said that “Books address issues that people need to talk about…, and maybe you don’t agree with the book, but you can’t broach that topic to even express your disapproval if you don’t read it.” She said she thinks most teachers are very mindful of what materials they bring into school.

“Books reflect different viewpoints. And that’s what an education is.” — Dr. Kathy Merlock Jackson, Professor of Communications

Book banning is often thought about in the context of popular dystopian media like “Fahrenheit 451.” While the reality is on a much smaller scale, the impact may still be large.

For many in the field of education, this raises concerns about the influence of book banning in K-12 on students who go on to pursue higher education.

Stephen Leist, the head librarian of Virginia Wesleyan University’s Hofheimer Library, said that the impact of book banning goes beyond academics.

For students heading to college, Leist said that book bans in grades K-12 can make them “ill-equipped to deal with the diversity that they are going to be thrown into.” He said that residential students must often share their living space with people who are very different from them, “and to make that year work, you have to figure out a way to coexist.”

He went on to say that part of the value of a liberal arts education, “whether it’s Virginia Wesleyan or any other institution of higher learning, is to challenge you. Challenge you to think more deeply about issues. Because this is what prepares you to engage with the world.”

Leist described their procedure for evaluating a book challenge at Hofheimer Library. He said that depending on where the book categorically falls, that respective librarian to that academic division is responsible for “making a decision whether or not the challenge has merit.”

About two years ago, Leist said he had a book challenge from a student worker concerned about an outdated racial term in the title. Leist said he discovered that this book was a chronological compendium of primary sources, such as articles from Black newspapers from the antebellum period to the Jim Crow era. He said this would be a necessary resource for students doing coursework on Black history in America. His final decision was to not withdraw it from circulation, and it is still available to check out today.

Leist recalled a story of a parent expressing to the Vice President of Academic Affairs at the time, Tim O’Rourke, their dissatisfaction with the assigned reading for Virginia Wesleyan University first-year students, “How to Tell Toledo from the Night Sky” by Lydia Netzer. In response, O’Rourke said, “if your son came here to have his current worldview confirmed, he came to the wrong place.”

By Lily Reslink

lbreslink@vwu.edu