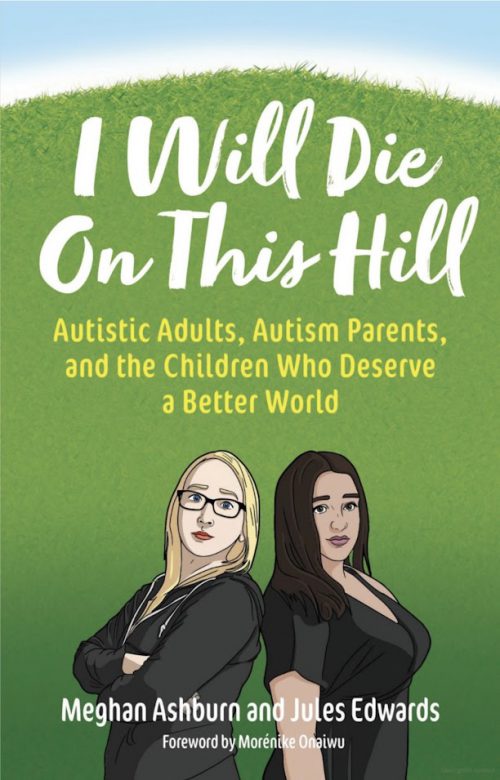

Featured Image: Meghan Ashburn & Jules Edwards |Courtesy

VWU alumna Meghan Ashburn ‘08 returned to campus on Oct. 21, along with co-author Jules Edwards, to share insight on their compiled book that touches heavily on the experiences of autistic adults. In light of this, students spoke on the experiences of autistic adults navigating higher education.

Senior Oliver Chauncey-Heine, president of the Disabled Student Union, said, “People think that I can’t be autistic because I’m verbose. Or that because I’m autistic I’m not capable of a college education. You’d think the two would cancel each other out; I’m not an alien, I’m just autistic.”

First-year Liam Castellano also shared their input on frustrating stereotypes. “Some of the misconceptions I see are that adults with autism are inherently immature or childish or have a lack of intelligence,” Castellano said.

As for how colleges can cater to diverse learners, Castellano said, “Some of my favorite projects that I’ve ever worked on in school were those where the teacher provided different options for different types of learners. This applies to neurotypical people too. Different people learn in different ways and work better in different situations.”

Castellano said that students benefit from having multiple methods to exemplify their learning “present or prove their knowledge.”

In the book, “I Will Die On This Hill: Autistic Adults, Autism Parents, and the Children Who Deserve a Better World,” author Meghan Ashburn spoke in depth on how the typical school system structure is not conducive to inclusivity.

Relating to Castellano’s sentiment, Asburn wrote in the book, “Instead of talking about [neurodiversity] as a deficit, we should approach the topic as a difference. All of us learn differently.”

She wrote that it is unnecessary to make a spectacle over extra areas of need because someone has a disability.

In Castellano’s experience, VWU offers this kind of support and inclusivity. “I think VWU as a whole… is also very accepting of different people of different backgrounds with different strengths and abilities,” Castellano said.

Ashburn echoed this statement. Having graduated from Virginia Wesleyan after struggling to find her footing at several other higher education institutions, Ashburn commented on the support systems that make this school favorable to diverse learners.

Co-authors Jules Edwards and Meghan Ashburn open the event with a discussion. Laila Jones | Marlin Chronicle

Jules Edwards and Ashburn, the co-authors of “I Will Die on this Hill,” expressed how impersonal the disability services are at other institutions, approaching support efforts like a checklist of requirements rather than responsiveness to individual needs.

Ashburn said the ideal structure for accommodations in education will be “person-centered,” and VWU has exemplified this. “I think that other colleges will have a lot to learn from this model,” Ashburn said.

However, the university experience is not entirely smooth sailing for those on the spectrum. Chauncey-Heine pointed out examples such as sensory issues caused by music blaring in the dining hall or the struggles in explaining executive function issues to professors. There will always be areas of improvement, but neurodiverse students continue to have the space to pursue their goals at VWU.

Ashburn elaborates on the systems in place that have facilitated this environment. She said students often need simple modifications such as extra time for assignments or a different testing location, and requiring an extensive process to enact an elaborate disability support plan may only amplify the stigma around these services.

VWU’s approach to accommodations played a big part in her success here. Ashburn wrote in the book that after an eight-year journey to get her bachelor’s degree through four different colleges, she graduated magna cum laude.

The book signing hosted by Virginia Wesleyan allowed Ashburn to return to the university that helped make the book possible. There, both authors welcomed a range of supporters who listened as they reminisced about the writing process, read excerpts and answered questions.

Chauncey-Heine expressed gratitude for the opportunity to meet the authors and hear their experience. As an autistic student, Chauncey-Heine said it made them “feel really heard.”

In the opening discussion, Ashburn said, “Everyone wants to do what’s best for the autistic people in their lives, but everybody has a different idea of what ‘best’ is.”

Ashburn and Edwards explained their goal of using this book as a platform to discuss diverse perspectives, particularly from people with autism.

The book discussed how the typical archetype for autism consists of young white boys.

Edwards wrote, “Autism as a diagnosis exists based on the research of young white boys from affluent and well-connected families.” Referencing data from the CDC, she said, “There are enormous disparities in identifying autistic people of color and autistic girls and nonbinary people.”

As an adult woman of color with multi-racial children, Edwards explained how belonging to certain intersecting identities can prevent an autism diagnosis from coming as naturally. This proved true in her own life.

For herself, a diagnosis did not take place until age 32 as she recognized signs in herself that aligned with the research she did for her sons.

Since the diagnosis process often begins in childhood, exploring autism diagnoses as a college-aged adult and beyond can be quite unconventional. Edwards said it is not uncommon for a diagnosis journey to begin by resonating with posts online. “I think one of the pathways for adults finding out that they’re autistic or neurodivergent in any form really, these days, is relatable memes on the internet,” Edwards said.

Edwards spoke on the feelings of inadequacy that can pop up for those who lack a diagnosis in which they can attribute their struggles. “Something that’s really common is autistic people are unnecessarily hard on ourselves,” Edwards said, especially for individuals who receive a diagnosis later in life.

“Once you get a diagnosis as an adult, you get this whole new lens and you look back on your life and things click,” she said.

While Edwards said not everyone is inclined to seek clinical diagnosis, it creates helpful context for some. “It helps people go through the process of accepting themselves and their past and their history and building a better future for themselves,” Edwards said.

There is no one way to be autistic, nor is there one way to be an advocate.

As for college students, “[College] is an incredible opportunity for neurodivergent students and neurotypical students to just kind of learn not just the academics, but how to be inclusive and how to be good people,” Edwards said.

Ashburn said to help make a better world, “keep the dialogue open, and keep an attitude of curiosity.”

“In my culture, in Ojibwe, there’s this word called mino-bimaadiziwin, and it means live in a good way, or live a good life,” Edwards said. She described how this mindset can act as the foundation for everyday living.

“Every day you make decisions about how you want to show up in the world, and you want to make decisions that are good for not only yourself, but the people around you and the people who come after you,” Edwards said.

By Lily Reslink