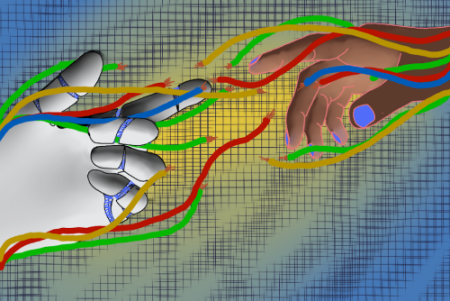

Featured Image: Mars Johnson | Marlin Chronicle

ChatGPT and other large language models, colloquially known as AI, are becoming a part of classroom life, whether or not it’s welcome. Students use it to cheat or to study, and sometimes aren’t certain what use falls under which category. Professors consider it, at turns, a useful tool and a threat to student learning.

ChatGPT is the best-known large language model (LLM), produced by the company OpenAI. Competitors include Google and Meta. LLMs produce answers to a question based on a large learning base skimmed from the internet and other sources.

“[ChatGPT was] like you woke up one morning and it was a new world,” Professor of Communication and Media Stuart Minnis said.

Minnis, along with other professors, has had to move online exams to physical paper due to cheating using LLMs, which possess a large knowledge base. However, Minnis also expressed hope that it would be positive for students and educators alike.

“[AI] could reinvent a lot of things, including what counts as work,” Minnis said. He described it having a use in the classroom as a first copy-editor or research assistant, but said that he doesn’t know how it’s going to be used in the future.

No matter what role it plays in future classrooms, it is already a large part of many students’ lives today.

Junior Sasha LaPonte used it to practice presentations for one of her classes. She asked ChatGPT to produce presentations similar in format to hers, but on random topics, and then would practice presenting those.

“It was very nice to not have to worry if what I’m reading is true or not, just to practice the activity,” LaPonte said.

Assistant Professor of Computer Science Abdullah Al-Alaj had a student, alumnus Jack Mowatt, do research on ChatGPT.

“For simple tasks, ChatGPT showed a remarkable aptitude,” Al-Alaj said. However, the research showed that for harder tasks it was a little more variable. It was tested on various difficulties of programming assignments for different class levels.

LLMs such as ChatGPT have information on many subjects, which they can rephrase in a way that is largely undetectable to plagiarism checkers. To less scrupulous students, cheating with ChatGPT would be tempting. According to Minnis, it can produce results that earn at least partial credit for almost no work, even less than other forms of cheating. However, it is far from safe.

“Some solutions provided by ChatGPT are putting the students in a risky situation,” Al-Alaj said, whose students generally write code for their tests. He gave the example of ChatGPT providing code solutions for a course that worked, but were too advanced or didn’t use the method required by the course. Getting caught wasn’t the only thing that was risky about cheating, though.

“I think a student might be tempted to use GPT as a shortcut, missing out on the learning experience,” Al-Alaj said.

Al-Alaj said that in his classroom, students are allowed to use LLMs to “customize their learning,” but that he was waiting for the official university policy before he made any hard rules.

In humanities courses, where there is no easy way to determine what is too advanced for a student, there are other dangers.

“Hallucination is real,” Al-Alaj said, referring to a fault of LLMs to occasionally state outright wrong information as if it was correct.

Hallucination is a result of the LLM not actually searching for a correct response, just the most likely. For example, Minnis mentioned a time when several students gave the same incorrect answer to a question.

Even if people are understandably scared of the change this will cause in education and the world at large, the technology must be understood, because it isn’t going anywhere.

“It’s naive to think we can put this genie back in the bottle,” Minnis said. “This technology is here to stay.”

Cheating is perhaps the most obvious implementation of this technology into the classroom, but even if it isn’t used for that, it will be used in other ways.

“If it can be used to cheat, it can write emails,” Minnis said.

He said he can imagine it as an editorial assistant, helping to refine a thesis or organize ideas. One example Minnis mentioned was taking abstracts of scientific papers and simplifying them to be understandable to an average person. He said that the line between it helping and it doing work for a student is thin.

Al-Alaj, on the other hand, mentioned teachers that used it as a virtual teaching assistant that could answer simple questions by students. He described it as a useful tool for personalized learning, but worries about the data risks it may cause.

Al-Alaj was clear that he doesn’t see the human educator being replaced, needing to teach skills that can only be taught by other people, such as social skills and other forms of development.

“It is scary from an educational viewpoint,” Minnis said. “We can’t just do what we’ve always done before.”

He described it changing the workplace too, both removing and introducing new jobs. Educationally, though, he said the goal is clear: make sure the tool is used to do what “education at its best” does, which is to help people understand better.

Even past the classroom and the workplace, both of which LLMs are likely going to have huge effects on, ChatGPT can be used for leisure activities and play as well.

For instance, in addition to using ChatGPT to practice presentations, LaPonte uses it to play Dungeons & Dragons. A tabletop role-playing game, D&D involves multiple players and a person who adjudicates the world and what the players do, colloquially called the Game Master. LaPonte asked ChatGPT to play all the parts except for her character.

“It actually listens surprisingly well,” LaPonte said. She mentioned that it was responsive and allowed her to play the game well, but she did complain that it was rather generic in its world.

ChatGPT is already having effects on classrooms, as any student who had to take a written essay for the first time since high school or who had to write code out on paper can attest. However, the future of the technology remains unclear.

“I wish I could predict the future,” Minnis said. “The world is about to change.”

By Victoria Haneline

vfhaneline1@vwu.edu